Animism is an ancient worldview at the root of spirituality and religion that views humans as part of an interconnected web of life that unites the seen and unseen worlds.

The word Animism derives from the Latin root Anima, which means breath, spirit and life.

Anima is similar to Prana in the Vedic tradition, Chi in the Taoist tradition and the universal spiritual force referred to as the Great Spirit and many other names in Indigenous traditions.

Celtic Druids call this spiritual life-force Nwyfre, the Algonquians call it Manitou and the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) call it Orenda.

Greek philosopher Plato called this universal spiritual force the Anima Mundi in his philosophical treatise Timaeus on the origins and workings of the Universe:

“This world is indeed a living being endowed with a soul and intelligence, a single visible living entity containing all other living entities, which by their nature are all related.”

Interestingly, Plato transcribed the words of his teacher Socrates — widely considered the father of Western philosophy — who refused to write anything down because he believed that writing was not an effective means of communicating knowledge and would lead to a misunderstanding of his ideas.

In a striking similarity to oral storytelling cultures that are commonly associated with Animism, Socrates believed that real knowledge is:

“Engraved in the soul of the learner; learning takes place when the word is written in the soul; writing is just an image. Writing is nothing but the pharmakon, the remedy, to remember what they learned before through dialectical discussion.”

Literate Logos And Oral Mythos

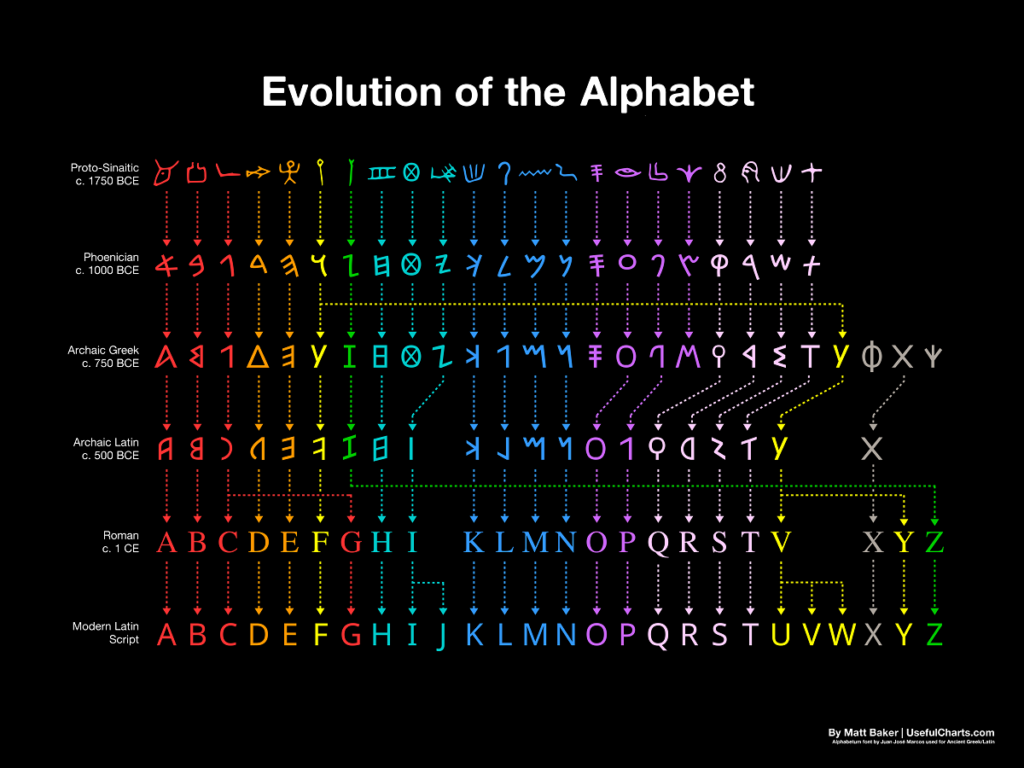

Cultural ecologist David Abram has a fascinating perspective on how the evolution of the alphabet has shaped our perception of the world (Image Source: Useful Charts).

While oral storytelling cultures usually share an animistic mythology and cosmology that revered this universal spiritual force found in all living beings, modern literate cultures tend to be much more identified with what the ancient Greeks called logos (reason, logic, abstraction) and often struggle to comprehend the value of mythos (intuition, feeling, mythology).

In modern times, with the advent of mass schooling and mass media, the way we think and interact with the world has fundamentally changed through the adoption of a strict reductionist materialism that disconnects us from the sense of the sacred that is found in mythos and our own ancestral traditions.

The hyper-rationalism and mechanistic reductionism of the Western materialist worldview prevailing today is unique in world history with a strange “soulless” materialistic view of the Universe as an indifferent clockwork-like machine or code-based simulation.

I believe the result is our collective sense of the sacred has been severed and replaced with an insatiable drive for scientific progress and material consumption without any sense of limits or responsibility.

The Spiritual Ecology of Animism

Animism is not an abstract concept but a direct way of feeling and experiencing life.

The revival of the living, breathing language of Animism is vital for reversing climate change and building a regenerative culture in which we can believe in the future again.

Animism is a deeply rooted value-system based on respect for the land, reverence for all life and relating to the more-than-human world as a living being infused with sentience.

The practice of Animism is about cultivating a relationship with what Plato called the “Anima Mundi” or the world soul.

The world soul is, according to several systems of thought, an intrinsic connection between all living things on the planet, which relates to our world in much the same way as the soul is connected to the human body.

Animism provides a spiritual ecology to reorient people for earth stewardship and building a regenerative culture.

Spirit can be conceptualized as all the invisible threads that connect people with the more-the-human world and elements of nature that make the miracle of life on Earth possible.

Using the breath, we can experience this spiritual ecology directly through our heart. Breath awareness and rhythmic breathing offers a powerful gateway to open our sensory gating channels to see through the “eyes of the heart ” and move past habitual patterns of self-referential thinking.

Through practices of conscious breathing and heartfelt mindful awareness, we can ground ourselves in the “felt presence” of our immediate experience and start to perceive the world without the filters of our judgements, labels and conditioning.

The Animistic Worldview Explained

This 4-minute video does a good job of describing the general Animistic worldview.

Animism, Biophilia And Enriching Sensory Experience

Animism is defined on Wikipedia as:

1. The attribution of a spirit to plants, inanimate objects, and natural phenomena.

2. The belief in a supernatural power that organizes and animates the material universe.

This is a good definition by and for modern analytical minds. But Animism is something much deeper and profound.

Ultimately, Animism is about the development and enrichment of sensory experience and the cultivation of a love of nature that is often referred to as Biophilia by the famed ecologist E.O. Wilson.

Animism doesn’t necessarily describe a belief system. However, every tribe and culture with an animistic cosmology has a different mythology and belief system rooted in the unique characteristics of their land.

The practice of Animism involves developing an embodied connection with the natural elements that give us life, as well as a heartfelt relationship with the other living creatures in the web of life.

At its core, the practice of Animism is about cultivating a perception of reality that goes beyond the compulsive labelling, comparison and judgement of the analytical mind.

Nature becomes much more alive to our senses when we begin to explore the world with child-like wonder again and expand our awareness beyond the limitations of language and the preconceptions of the analytical mind.

Delving into the practice of animistic perception through mindful hiking and mindful awareness practices can help to foster an intuitive knowing of our interconnection and kinship with all living beings.

All living things we experience through our senses breathe and create subtle electromagnetic fields that we can interact with through our hearts. Developing this feeling sense starts by gradually expanding the “sensory gating” of cultural conditioning and developing the perceptual acuity of our senses.

The God Head And How I Got Into Studying Animism

Growing up with Cornish ancestry, I’ve always been fascinated by the animistic myths and legends of the ancient Celtic priesthood called the Druids.

Once the dominant culture of the British Isles, they were conquered by the Roman Empire and then overrun by the Anglo-Saxon warrior tribes from Northern Germany who colonized the British Isles in the 5th century.

It took nearly 1,000 years to subjugate the six Celtic Nations of the British Isles (Brittany, Ireland, Cornwall, Wales, Scotland and the Isle of Man) before this divide-and-conquer mass colonization strategy used by the English spread across the world.

I was always interested in the magic and mystery of the animistic language of the Druids. I’ve also been fascinated with the history behind how the modern world was formed through an occult war against nature, and the tradition of oral storytelling by Indigenous people who are the keepers of the Earth.

These interests prompted me to study ancient history and the rise of the modern world at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Vancouver, Canada.

At UBC, I sought refuge from stress and the boredom of lectures in the Pacific Spirit rainforest that surrounds the campus and Stanley Park a short bike ride away.

My interest in exploring Animism was sparked by the discovery of the God Head, a mysterious carving buried in the rainforests of Stanley Park.

Fascinated by this place of peace, beauty and tranquillity in the forest, I began making a regular pilgrimage to meditate and contemplate silently in the forest.

The God Head (pictured from different angles in this post) was carved by an anonymous Indigenous carver in the early 1970s out of the stump of an old-growth Western Red Cedar, which is considered the “Tree of Life,” in local Coast Salish culture.

The Coast Salish is a group of ethnically and linguistically related Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast living in British Columbia. The Western Red Cedar tree is highly valued and revered because of a natural preservative in the cedar wood that slows decay, which makes it ideal material for building longhouses, canoes, and many of the largest totem poles that still stand today.

On my regular trips to the God Head, I was continually awe-struck by this beautiful carving that combines human ingenuity and the living art of nature with different mushrooms, bushes, ferns and lichen growing out of it as the seasons change.

For me, it became a powerful symbol of the dualities of life and how our existence is a balancing act, and the interplay between seemingly opposing forces that upon deeper inspection are closely interconnected. These forces include:

1. Humans and nature

2. Art and science

3. Life and death

4. Growth and decay

5. Wildness and domestication

6. Reality and illusion

7. Matter and spirit

This sparked my curiosity to learn more about the ancient and modern history of Animism and spend long periods of time camping in the backcountry to explore this form of spiritual or nondual ecology through awe, mindfulness and deep ecology practices.

The Modern History of Animism

The first modern scientists and cultural anthropologists that spread out across the world with European nautical explorers were perplexed by Indigenous worldviews.

But Animism actually has a long history in Western culture going back (and beyond) to the ancient priesthood known as the Druids in Western Europe and other animistic cultures that were conquered and colonized over time.

Today, Western science and Enlightenment rationalism have relegated Animism to the margins. However, it is making a comeback in this age of mass alienation from nature, relativistic nihilism and climate breakdown.

The avalanche of data, statistics and academic papers from 100,000-plus scientific studies and tens of billions of dollars spent on climate change research doesn’t speak to most people’s hearts, nor has it mobilized the kind of collective action we need to save ourselves.

What we need is to create a new story.

I believe the modern Western way of perceiving the world as a detached observer in a reductionist, mechanistic and ultimately meaningless Universe is at the root of the crisis of consciousness and global biodiversity collapse happening today.

To challenge this destructive worldview of materialism, there is an awakening of people who are learning to perceive the world through the heart again and embody ancient teachings that can set them free from the limited abstractions and restlessness of the analytical mind.

The modern conception of Animism was first developed by German chemist, physician and philosopher Georg E. Stahl in 1708 as Animismus, which grew out of a branch of science called Vitalism.

Vitalism is the belief that a spiritual force is vital to life and that many diseases have spiritual causes.

In 1869, English anthropologist Edward Taylor read Stahl’s theory and coined the word Animism for the belief and value systems of pre-agricultural, nature-based tribal people.

It essentially denotes a belief system in which human beings are not separate from the environments from which they have evolved.

In Animism, all life is perceived as being alive and interconnected in a reciprocal relationship with other living beings.

In the last two decades, the traditional animistic worldview that all living things are our ancestors has been validated by evolutionary biology tracing our DNA to the beginning of life on Planet Earth 3.8 billion years ago.

Animism has been recognized by cultural ecologist David Abram as a phenomenological experience, which denotes a sensory experience that is often deprogrammed out of people by heavy reliance on the written language, rote learning methods and hypnotic screens.

In 2006, Alf Hornborg, a professor of Human Ecology at Lunds Universitet in Sweden, published data from anthropologists exploring the theory that Animism is a basic human psychological need.

Interestingly, modern psychology dating back to Sigmund Freud’s book Totem and Taboo has researched Animism. Today it is widely accepted by psychologists that children are naturally animistic, but this way of seeing and interacting with the world is often lost in the process of Western schooling.

From consciousness and neuroscience research, there is also an emerging scientific theory of “Panpsychism,” which posits that there is an all-pervading sentience and consciousness at every level of the Universe from the microcosm to macrocosm.

Animism challenges the current Western scientific worldview that emphasizes the quantitative over the qualitative and exhibits a strong tendency toward the denial of the existence of natural forces that can’t be easily measured through current technological instruments.

Interestingly, many conventional scientists are coming full circle back to Animism with recent discoveries that the natural world is infused with sentience, intelligence and communication binding it into whole “networked” communities that operate as if self-aware.

This is starting to be reflected in the development of a more holistic science and the growing importance of systems thinking.

The Ancient History of Animism

Animism is a language much older than written words and our ancestors were animists for most of human history.

What we call agricultural civilization with its strict hierarchies, organized religions and secretive priesthoods started in the late Bronze Age less than 6,000 years ago.

They arose out of the early empires of Mesopotamia and the Far East, which grew from the large agricultural surpluses that only intensive agriculture can produce.

Yet, beyond the time scale of written history, our ancestors have had the self-awareness and language to communicate with each other and use Stone Age tools as hunter-gatherers for nearly 2.6 million years.

The monotheistic cultures that revere the written words of their scriptures above all else are a very recent phenomenon in human history.

The militant literalism of modern fundamentalist and evangelical movements are even more recent at less than 200 years old. They have largely grown out of a reaction against the changes of modernity that have disrupted rural life and have led to poverty in much of the countryside today.

While the Abrahamic monotheistic religions have colonized animistic cultures throughout their history, today there is a growing reconciliation with Indigenous ways of knowing.

Young people today are well-aware of the historical atrocities committed in the name of God upon innocent people and that the scale of our planetary ecological crisis necessitates a new way of thinking and being in connection to nature.

Science and religion alone won’t save us in this time of transition and crossroads for humanity.

We also need to experience the Earth again as a vital and sentient living being and explore the interconnected intelligence of nature.

The Return of Animism

A return to the mythological Garden of Eden or the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse?

Today, we desperately need a new regenerative culture where ecology isn’t merely about analyzing the world and accumulating more data about our problematic relationship with the natural world but fundamentally changing that relationship.

The animistic worldview that all living creatures are our relatives is now being validated by modern science and evolutionary biology. Yet as a society, we remain profoundly disconnected from the land and stuck in the self-referential mental clutter of anxiety, separation and abstraction.

It is now typical in highly-developed countries for people to spend 90% of their days sedentary indoors and as much as 10+ hours a day staring at a screen. Even normally high-energy kids are now mostly sedentary today.

To make matter worse, the increasing dominance of electronic media has ushered in what Canadian media philosopher Marshall McLuhan called a “global village” back in the 1970s.

While this sounds utopian and there are many positives of the emerging global village, McLuhan actually argued that electronic media would create a new form of digital-mediated tribalism where people would have extreme concern with everybody else’s business and the result would be disharmony, polarization and loss of privacy.

Sounds a lot like the cultural wars and thumb-scrolling voyeurism of the last decade that have arisen alongside the mass adoption of smartphones and social media.

If we are to overcome our differences, solve our existential climate crisis and navigate beyond strict materialism to a post-consumer culture, we are going to need a spiritual ecology that offers a new way of seeing the world with more mindfulness, compassion and appreciation of the interconnectedness and interdependence of life.

Developing a stronger ritual connection to the living, breathing world of Animism where each of us can experience the elemental life-giving forces of air, water, fire and earth as sacred again can help reconnect us with the lost ancient wisdom of our ancestors.

We need to find a balance and harmony of what only appear to be opposites such as logos and mythos, materialism and animism, science and religion, liberal and conservative, humans and nature.

I believe we are at the potential dawning of a new epoch of human ingenuity and creative possibility. There is a new animism rising within our machines known as artificial intelligence. While this development could ultimately mean the destruction of the human race as we know it, it could also lead to a better, more sustainable world if we develop the consciousness to use it wisely.

This time of transition challenges each of us to shift our perception of who we are, where we come from, and why we are here to embrace a larger ecological self.

Through a different way of perceiving ourselves in the world, we can develop new ways to engage in awe and reverence with the miracle we call life and work together in synergy with the more-than-human world to build a regenerative culture that will thrive for generations to come.

- Reconnect To Your Original Nature Through Awe And Wonder - April 17, 2024

- Pasqueflower: A Spring Wildflower That Symbolizes Rebirth - April 5, 2024

- Deep Embodiment And The Flow of Embodied Awareness - April 1, 2024